If you’re muted in an online video game, does that violate your Civil Rights?

At first I thought, duh, no, recalling all of my experiences dealing with internet trolls or players clearly violating a user agreement to cause chaos. Typically, if you’re rude or doing something that you aren’t supposed to do in an MMO and get kicked out, you deserve it. By using a privately owned platform, you’re consenting to their rules and regulations, and therefore agreeing to their policies as to what would warrant removal from a site. (8-year olds cursing on Club Penguin comes to mind.)

A recent Kotaku article details a situation in which Runescape player and streamer Amro Elansari sued Jagex, the game’s developer, after the company permanently muted him in the game in 2019. Elansari claimed this was a “violation of due process,” “discrimination,” and attacked his “free speech.” Elansari’s case failed in court, of course, and was not deemed a violation of Civil Rights. He had little ground to base his case off of, especially after accepting the Runescape user agreement prompted to every player upon signup.

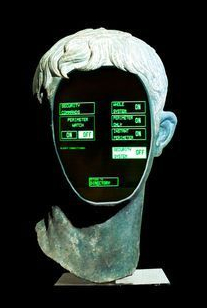

While Elansari’s situation has minimal repercussions, it made me wonder how this situation would play out in a future heavily dominated by VR, AR, and other integrated tech. I can’t help but consider the isolating effects of Black Mirror’s episode White Christmas in which a character is essentially “blocked” from society. Due to a neural chip, the blocked man appears to everyone as a blurred out, static-y silhouette, and to the man, everyone else appears as the same silhouette with all conversations muted. By our standards, permanent isolation is a highly unethical, cruel punishment that would certainly violate our Civil Rights.

As technology continues to be seamlessly integrated into our everyday experiences, I believe that situations like Elansari’s could quickly sneak up on us and begin happening at a larger scale. Sure, it’s a bummer to be kicked off of Twitter or Instagram, but what if in the not-so-distant future, a large tech company facilitated all of our interactions? (Similar to Ready Player One, perhaps.) To be blocked or removed from a platform like that would be detrimental to one’s social health and wellbeing.

Our current MMO platforms and social media sites have donned government-like rules, as they are the kings of their small slice of digital reality, but have failed to implement strong and consistent government-like oversight to properly deal with situations like these that could extend into the future with heavier ramifications.

Our current MMO platforms and social media sites have donned government-like rules, as they are the kings of their small slice of digital reality, but have failed to implement strong and consistent government-like oversight to properly deal with situations like these that could extend into the future with heavier ramifications.

For now, Elansari’s situation and others similar to his may elicit an eye roll or a “he deserved it.” Yet, with the current speed and direction technology is headed in, and the ways in which it is melding with and changing our society and interactions, we may have to revisit our user agreements*.

“Once you have an augmented reality display, you don’t need any other form of display. Your smart phone does not need a screen. You don’t need a tablet. You don’t need a TV. You just take the screen with you on your glasses wherever you go.” -Tim Sweeney

*Speaking of user agreements…

Check out another post dedicated solely to the dark practices of user agreements!

Learn about a fun terms of service Google Chrome extension here.

In 1961, IBM created the first computer, the IBM 7094, to sing using computer speech synthesis. The song of choice? Daisy Bell. (You can listen to it

In 1961, IBM created the first computer, the IBM 7094, to sing using computer speech synthesis. The song of choice? Daisy Bell. (You can listen to it  Perhaps people determine that the ability to sing marks intelligence in their machines. Perhaps when we can ask our machines any question imaginable, ‘can you sing me a song?’ is one of the first questions that comes to mind. Or maybe the ability to sing is a sign of status, giving a user or creator the ability to say that their machine can sing a song while another’s cannot.

Perhaps people determine that the ability to sing marks intelligence in their machines. Perhaps when we can ask our machines any question imaginable, ‘can you sing me a song?’ is one of the first questions that comes to mind. Or maybe the ability to sing is a sign of status, giving a user or creator the ability to say that their machine can sing a song while another’s cannot. Rovio has begun to introduce a combination AI to help build and test their latest Angry Birds game. Game design is a delicate balance; make a game too easy, and consumers will complain that it’s too similar to previous games or not challenging enough. Make a game too difficult, and people will lose attention and quit. In a game where the mechanics are quite simple to grasp (you’re launching birds with the tap of a finger to hit and kill things), as most mobile games are, it’s difficult to solve the “fun factor” formula.

Rovio has begun to introduce a combination AI to help build and test their latest Angry Birds game. Game design is a delicate balance; make a game too easy, and consumers will complain that it’s too similar to previous games or not challenging enough. Make a game too difficult, and people will lose attention and quit. In a game where the mechanics are quite simple to grasp (you’re launching birds with the tap of a finger to hit and kill things), as most mobile games are, it’s difficult to solve the “fun factor” formula. Will Wright, a renowned American video game designer, predicted in 2005 at a Game Developers Conference that “a game development company that could replace some of the artists and designers with algorithms would have a competitive advantage” (

Will Wright, a renowned American video game designer, predicted in 2005 at a Game Developers Conference that “a game development company that could replace some of the artists and designers with algorithms would have a competitive advantage” (

Perhaps you’re hesitant to follow a robot who exists solely to share images full of product placement. But many other people aren’t deterred. A majority of followers flock towards these virtual influencers with an interest in the fact that these influencers are not human. (Perhaps it’s because the coming of age generation grew up watching Hannah Montana and we’re all accepting of fake celebrity personas.) These Instagram influencers were not the beginning of made-up digital content, however; the musical group Gorillaz was founded in 1998 as a virtual band, and won their first Grammy over a decade ago. In 2016, Louis Vuitton hired a character from Final Fantasy for an advertising campaign. Last month, Miley Cyrus adopted yet another persona, Ashley O, a character from a Black Mirror episode, releasing a single that became the #1 pop song in June. Amanda Ford, creative director at integrated agency Ready Set Rocket, sums it up well: “People know the world we’re living in, nothing we see on social media is really authentic and no one is being their real self, so whether it’s a person with a beating heart or a robot, I don’t think it matters anymore.”

Perhaps you’re hesitant to follow a robot who exists solely to share images full of product placement. But many other people aren’t deterred. A majority of followers flock towards these virtual influencers with an interest in the fact that these influencers are not human. (Perhaps it’s because the coming of age generation grew up watching Hannah Montana and we’re all accepting of fake celebrity personas.) These Instagram influencers were not the beginning of made-up digital content, however; the musical group Gorillaz was founded in 1998 as a virtual band, and won their first Grammy over a decade ago. In 2016, Louis Vuitton hired a character from Final Fantasy for an advertising campaign. Last month, Miley Cyrus adopted yet another persona, Ashley O, a character from a Black Mirror episode, releasing a single that became the #1 pop song in June. Amanda Ford, creative director at integrated agency Ready Set Rocket, sums it up well: “People know the world we’re living in, nothing we see on social media is really authentic and no one is being their real self, so whether it’s a person with a beating heart or a robot, I don’t think it matters anymore.” In 1986, a group of scientists reconstructed the neural wiring of a roundworm, completing a diagram with 302 neurons and roughly 7,000 neural connections. (You can see the full diagram

In 1986, a group of scientists reconstructed the neural wiring of a roundworm, completing a diagram with 302 neurons and roughly 7,000 neural connections. (You can see the full diagram  With discoveries and advancements such as these, it’s only natural that we turn to science fiction to compare myth with reality. If you were to one day upload your brain to the cloud or pay for its preservation, how can you ensure the outcome? For example, will your consciousness, you right now, be transferred to an electronic database? Or will your consciousness merely be copied, so that while you die, a replica of you-which-is-not-you lives on, thanks to your sacrifice? Consider these scenarios:

With discoveries and advancements such as these, it’s only natural that we turn to science fiction to compare myth with reality. If you were to one day upload your brain to the cloud or pay for its preservation, how can you ensure the outcome? For example, will your consciousness, you right now, be transferred to an electronic database? Or will your consciousness merely be copied, so that while you die, a replica of you-which-is-not-you lives on, thanks to your sacrifice? Consider these scenarios: The timeline of a human brain-internet connection is rather short. In 2017, human brainwaves were streamed live on the internet via a Raspberry Pi (dubbed the ‘

The timeline of a human brain-internet connection is rather short. In 2017, human brainwaves were streamed live on the internet via a Raspberry Pi (dubbed the ‘ Just a couple days ago, Elon Musk unveiled

Just a couple days ago, Elon Musk unveiled

There is a surprisingly large variety in the ways websites try to trick users to the point where I have to give these “dark UX designers” props; although they’re using their powers for evil, their tactics are still very creative. The senate is working to pass a

There is a surprisingly large variety in the ways websites try to trick users to the point where I have to give these “dark UX designers” props; although they’re using their powers for evil, their tactics are still very creative. The senate is working to pass a  The term “deepfake” was coined in December of 2017 by a Reddit user in the thread r/deepfake, a place where creators could post their made-up content, most of which involved the creation of fake pornography. The thread was banned in 2018, although a clean deepfake thread has reemerged on the site, consisting of made-up political hoaxes, fake news, and celebrity videos. Deepfakes have since been banned on other websites, although upholding the ban proves difficult. As this internet community grew, so did the deepfake’s academic counterpart: in 2017, computer scientists at academic institutions across the globe were studying computer vision, which focuses on AI and the processing of video and imagery in computers. As both communities advanced, so did their technology.

The term “deepfake” was coined in December of 2017 by a Reddit user in the thread r/deepfake, a place where creators could post their made-up content, most of which involved the creation of fake pornography. The thread was banned in 2018, although a clean deepfake thread has reemerged on the site, consisting of made-up political hoaxes, fake news, and celebrity videos. Deepfakes have since been banned on other websites, although upholding the ban proves difficult. As this internet community grew, so did the deepfake’s academic counterpart: in 2017, computer scientists at academic institutions across the globe were studying computer vision, which focuses on AI and the processing of video and imagery in computers. As both communities advanced, so did their technology. Are they right? Should their campaign managers monitor the internet for deepfakes? Should it fall into the hands of another to keep the lid on deepfakes? Governments across the globe are treating this fake media as a real threat to security; China is considering banning them altogether, and the U.S. is invested in countering them. Before high-quality deepfakes emerged in 2017, researchers have been warning officials that these computer-generated human syntheses would undermine public trust in the media.

Are they right? Should their campaign managers monitor the internet for deepfakes? Should it fall into the hands of another to keep the lid on deepfakes? Governments across the globe are treating this fake media as a real threat to security; China is considering banning them altogether, and the U.S. is invested in countering them. Before high-quality deepfakes emerged in 2017, researchers have been warning officials that these computer-generated human syntheses would undermine public trust in the media. Your digital footprint is much more visible than you think it is. Ads and content are steered towards us based on algorithms from other search results or clicks across the World Wide Web across all of our smart devices. Nowadays, with the amount of sites that require us to create accounts, agree to user policies, or provide other kinds of information (location, whether accessing a site via phone/tablet/computer, etc.), privacy has become more about controlling the data collected on us rather than stopping data collection, which is very close to impossible.

Your digital footprint is much more visible than you think it is. Ads and content are steered towards us based on algorithms from other search results or clicks across the World Wide Web across all of our smart devices. Nowadays, with the amount of sites that require us to create accounts, agree to user policies, or provide other kinds of information (location, whether accessing a site via phone/tablet/computer, etc.), privacy has become more about controlling the data collected on us rather than stopping data collection, which is very close to impossible. On average, you would have to spend

On average, you would have to spend  At the start of the 20th century in the midst of the Second Industrial Revolution French nobleman Marquis de Castellane, appalled by the emergence of the push button, remarked, “Do you not think that is prodigious diffusion of mechanism is likely to render the world terribly monotonous and fastidious? To deal no longer with men, but to be dependent on things!” (If only he could see us now.) Buttons were suddenly a magical gateway to alerting others of fire, honking car horns, and opening elevators. The act of pushing a button came to signify comfort, convenience and control, while those wary of technological advancements in the early 1900s viewed it as alienating or a sign of lacking skill.

At the start of the 20th century in the midst of the Second Industrial Revolution French nobleman Marquis de Castellane, appalled by the emergence of the push button, remarked, “Do you not think that is prodigious diffusion of mechanism is likely to render the world terribly monotonous and fastidious? To deal no longer with men, but to be dependent on things!” (If only he could see us now.) Buttons were suddenly a magical gateway to alerting others of fire, honking car horns, and opening elevators. The act of pushing a button came to signify comfort, convenience and control, while those wary of technological advancements in the early 1900s viewed it as alienating or a sign of lacking skill.